Why business majors play with crayons

My opinionated take on how top undergrad business programs like Michigan Ross fail to deliver an optimal business education.

Contrary to popular belief, business majors don’t just draw with crayons, play with legos, and perform basic addition all day. However, the reality isn’t that much better.

My name is Justin Guo. I’m a senior soon to graduate with a degree from the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, the #4 undergraduate business school in the country.

To quickly clarify, Ross is named after Stephen M. Ross (American businessman and Miami Dolphins owner) and is unaffiliated with fictional lawyer Mike Ross or American rapper Rick Ross. However, I believe the “Rick Ross School of Business” is an undeniably cooler name.

If this essay gets 10+ likes, I’ll create and distribute a petition to rename the program.

For being such a highly ranked program, I’ve been hearing a lot of peers and alumni express secret dissatisfaction with their education. After 4 years, I also found the curriculum to be fairly detached from reality, and now understand why “business school” abbreviates to “BS.” Much of these problems are Michigan-specific, but other parts reflect truths across other top undergrad business programs.

In this long-form essay, I share my pessimistic analysis on undergraduate business programs and advice I would tell college students looking for success.

Let’s get into it!

Before we start, I believe five main things drive ~90% of the total value for any modern business curriculum. If you disagree, that’s okay and I hope you have a great day.

Finding your thing (e.g. Finance, Strategy, Product)

Building technical, specialized skills in your thing (e.g. Excel, SQL, Figma)

Developing soft skills (e.g. Time Management, Communication, Storytelling)

Networking laterally with peers and vertically with alumni.

Exploring miscellaneous interests that you’re passionate about.

Although I won’t touch directly on all of these points, they’re helpful to keep in mind.

The anatomy of professional organizations

There are three actual reasons why Ross is ranked as the #4 undergrad business program in the country.

Business Frats, Finance Clubs, and Consulting Clubs.

You might be thinking, “I thought this essay was supposed to be about school! What do clubs have to do with anything?”

In principle, your train of thought is right. The premise of a business school critique should center around academics. However, these niche professional communities play such a crucial role in student success that I would be naive to redact their presence.

It also doesn’t matter whether you go to Ross, Wharton, Harvard, Haas, or McCombs. The same pattern occurs in programs all across the United States. Each business school has 5-15 top clubs, and almost the entire freshman and sophomore class is simultaneously trying to get in to them.

Club prestige is based on factors like placement, quality of education, culture, alumni network, and difficulty of acceptance. There is no official ranking list (someone unsuccessfully tried), but at Michigan, most students would generally agree on something along the lines of this:

Top Business Frats: Phi Chi Theta (PCT), Alpha Kappa Psi (AKPSI), Delta Sigma Pi (DSP), Phi Gamma Nu (PGN)

Top Finance Clubs: Michigan Interactive Investments (MII), Maize & Blue Endowment Fund (MBEF), Global Investments Committee (GIC), Michigan Investment Banking Club (MIBC), Alternative Investments Club (AIC), Victors Value Investments (VVI)

Top Consulting Clubs: Nexecon, MECC, BOND, APEX, 180 Degrees

These top organizations are basically factories that take in a class of high potential underclassmen as inputs and then produce professionally capable upperclassman as outputs. Without that much exaggeration, MII could probably take an 8th grader and land him a Morgan Stanley internship in 3 semesters.

Freshman year, I was lucky enough to get into both a strong business fraternity and strong finance club. Looking from the inside out, it’s painfully clear how members in these orgs have an ugly and disproportionate advantage over the average student.

The general business club journey looks something like this.

(1) Application: You undergo a rigorous multi-round “rush” process (essays, case interviews, technical interviews, networking) to screen for social and professional fit. Usually, you’re competing against 100 to 400 applicants with acceptance rates from 5-20%. This process almost exactly mirrors applying for selective jobs in the real world.

Video Credit: @thatsmyboyjacob

(2) Learning: You spend your first semester absorbing every piece of knowledge you possibly can. Depending on the club, these include a high concentration of professional workshops, stock pitches, client projects, socials, coffee chats, and education sessions. You also begin to develop close-knit informal relationships with members in the club, which become important later on.

(3) Recruiting: You recruit for an internship. When applying to firms, you leverage the club’s curated alumni network built over the last 10 to 25 years. When preparing for interviews, you spam mock interviews from upperclassman in your focus area. Throughout this whole process, your analyst class keeps you accountable, and your mentors tell you exactly what to do and when to do it.

Josh Hou wrote a highly underrated and insightful reflection on IB recruiting from UT Austin; it’s extremely similar to how a Ross student in a finance club would approach it.

(4) Paying it forward: Once you land a job, your role switches from a mentee to a mentor. Since you had tons of help throughout your recruiting process, the natural behavior is to continue paying it forward to those who need it. Contributing to your underclassmen friends’ success is a responsibility aligned with your best interests. The same principle continues even after graduation when you become an alumni.

These clubs create perpetual success and nepotism-esque pipelines through a virtuous cycle of giving back. The magic is all in a loop of mentorship.

So how does all this relate back to business school?

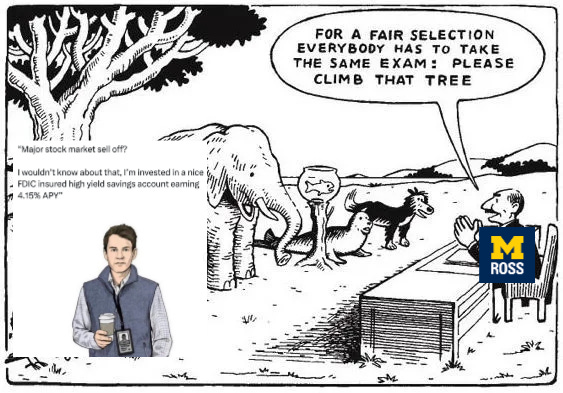

People are often impressed by Ross’s rankings on websites like US News or the classification as a “target school.” First of all, these rankings shouldn’t hold that much weight because half of them are made up. Second of all, contrary to popular belief, Ross doesn’t rank highly because of its academic curriculum.

I believe Ross ranks highly in SPITE of the academic curriculum.

Outside of the classroom, these clubs are the secret X-factors working behind the scenes to produce successful alumni. Every placement metric is inflated by how strong students involved in these extracurriculars are. If you aggregated data for Ross placement for top banks and consulting firms, I’d bet at least 70% of them are involved in 1+ of these clubs.

Without the extracurricular scene, I think Ross students would truthfully come out of undergrad without feeling like they learned very much at all.

On the bright side, this implies that Ross has a lot of potential for growth. If Michigan tends to recruit well with a mid curriculum, how great could the school be if we had a strong one that nurtured students’ interests?

In these next sections, let’s “double-click” (great buzzword) on life in the classroom.

Business students need specialization…

I want to quickly lay out my take on specialization before diving into what’s wrong with business degrees.

—

Take a shot every time I mention “specialization” and you might find yourself aggressively throwing up in a Wendy’s bathroom at 3:16 AM.

In my favorite Stanford life lecture How to Live an Asymmetric Life, Graham Weaver advises ambitious young people to find their thing and do it for decades.

This is why Lebron isn’t simultaneously practicing chess, ping pong, water polo, and basketball. When you focus on going deep in a narrow intersection of passion and aptitude, you build real leverage through the time and concentration necessary to acquire a rare skillset. The more leverage you have, the more valuable you become.

Deep specialization builds a moat for your professional identity: it empowers you to unlock insights on the knowledge frontier and increases the scarcity of your expertise.

Inversely, if you divide your focus to acquire surface-level skills in multiple areas, your hard work only puts you on par with novices. Surface-level basics naturally have a lower barrier to learn, which makes novices expendable and undifferentiated.

Counterargument: Generalists in multiple areas can better connect dots across domains.

My take: “Generalists” are only useful if they have specialized expertise in 1+ area. I think someone who is subpar at 3+ things is still next to useless because they have less dots (of which are lower quality) to connect in the first place.

Dan Hockenmaier wrote a great piece (Generalist Disease) tangential to this idea.

Put simply, most of the value is in specialization.

…therefore “business” majors shouldn’t exist.

It doesn’t matter if you dream of generating shareholder value (💰) or improving the political and economic state of the world (🤓). Every business student, regardless of their aspirations, wants a practical skillset in return for their time and tuition.

However, the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) completely fails to build practical skillsets because the curriculum is way too broad. Over four years, undergrads take 15 incoherent core classes that force investment bankers to learn the 4P’s and marketers to discount cash flows to their present value. Everyone with a clear professional interest wastes time in irrelevant areas.

To further understand why broad business degrees are unhelpful for career preparation, skim this list of jobs.

Finance: Investment Banking, Private Equity, Growth Equity, Venture Capital, Credit Investing, Accounting, Corporate Finance, Day Trading

Strategy: Management Consulting, Strategy Consulting, Corporate Strategy

Growth: Brand Marketing, Advertising, Product Marketing

Operations: Supply Chain Management, Project Management, Product Ops, Chief of Staff, Strategy & Ops, Business Ops, Program Management

Innovation: Entrepreneurship, Product Management

Talent: Talent Acquisition, HR Consulting

Sales: Business Development, Account Management, GTM, Customer Success, Partnerships, Door-to-Door Knife Salesman for Cutco

Not including day trading or knife salesman, these are 29 jobs in 7 vastly different business areas just off the top of my head. The business world is hugely complex and nuanced, which is precisely why “business” can not and should not be studied broadly.

Pick any of these functions besides HR consulting, and you could easily make a standalone 4-year curriculum to build a usable skillset for it.

(Kidding, shoutout to my HR consultants)

There is no skill called “business.”

— Naval Ravikant

The BBA is basically equivalent to if there was one major called “Engineering” that grouped computer science, mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, and robotics classes all under the same label.

Counterargument: A broad curriculum can help with the “explore” part of the explore-exploit dilemma. Students need to know what paths exist before specializing.

My take: Exploration is only a means to an end — its ultimate purpose is to allow you to pick your best option. Recruiting timelines shift earlier and earlier every year, and the lack of specialization blocks students from building skills for their respective internships in time.

Despite my passion for technology, some unrelated classes like financial accounting and business law did actually prove interesting and helpful. However, I found 70% (11 out of 15 classes) of the curriculum completely impractical. For my peers, I would guess the standard deviation of useful classes is ±2, regardless of professional interest.

Many of the useless business classes focus on fairy skills like management, leadership, and strategy. The reason behind this is that professors in these areas have limited actual experience in the subjects they teach. In fact, 11 out of my 14 core professors (approximately 78%) have less than a year of corporate experience. This makes it difficult to build credibility with students and connect the material to real life.

This candidly contributes to a remarkable amount of wasted time. If a 3-credit business class takes up around 110 hours per semester (GPT estimates 130-180, inclusive of study time), I’d win back 1210 hours or 50.42 days of my life that I could’ve instead spent scrolling on Instagram Reels to see great content like this.

Actual footage from inside a Ross class (follow @the_cams on TikTok!)

Academically, specialized electives provide the most value. TO412 and TO428 have both been exceptionally useful and interesting. However, the curriculum structure limits students from taking a sufficient number of them (especially if students choose to study abroad!)

Competition is for losers

In the business world, many top firms insist that employees should compete with each other to earn a bonus or avoid a layoff. Ross classes reflect this environment by allowing only <40% of students to get above an A- in each section.

The infamous Ross Curve, which can make a 75 an A or a 95 a B+ depending on how you performed against your peers, creates a cutthroat academic environment.

The core principle is to encourage students to outperform the people around them, which does give a little taste of the corporate world.

For one, this system mentally prepares students to recruit from ultra selective firms like McKinsey, Blackstone, and Northwestern Mutual (joke). These prestigious firms usually enforce a fixed number of offers for each school, so students who receive an interview directly compete against each other for a spot.

Secondly, the competitive environment helps some students think more critically about differentiation. For assessments, I didn’t always focus on how comprehensively I could actually learn the material. Rather, I often studied overlooked concepts that had a lower probability of being on the test, but would give me a definitive edge over my section if they were (e.g. qualitative material on a finance exam).

However, I believe the nasty drawbacks of the Ross Curve outweigh the benefits. Let me make this tangible through a hypothetical that my BBA friends often ask me.

“If there was a magic button that could screw over the grades of every other student in your section, would you press it if nobody knew?”

Without a moment of hesitation, I’m coming in like this:

I’m not an overtly selfish person - I once gave a homeless man in the Chicago Union Station half of my $16 smoothie bowl. How could I do such a thing?

Competition shifts your motivation away from an intrinsic desire to produce great work to an extrinsic pressure to outperform those around you. Because the core dynamics become optimized for performance over learning, students in this environment become more self-centered, myopic, and cold-blooded.

This attitude is probably where the derogatory “Rosshole” term comes from.

Rosshole: "A Michigan business student with a cutthroat attitude, access to supreme buildings, and a closet full of suits, and who never lets you forget about it."

Believe it or not, the competitive Rosshole stereotype is backed by hard data. Every year in the Michigan Marriage Pact, students fill out a demographic survey full of thought-provoking questions (e.g. how freaky are you on a scale from 1-5) to match with a compatible date on campus.

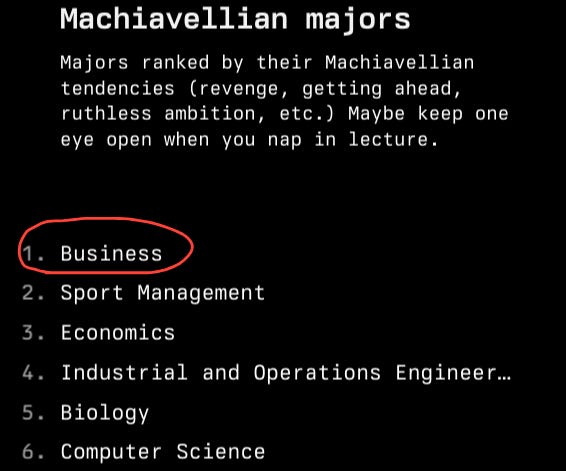

In their annual 2023 campus report, the Marriage Pact surveyed Machiavellian tendencies among the University of Michigan’s student body. Google defines these tendencies as “traits characterized by manipulation, deceit, and a focus on self-interest and power, often at the expense of others.”

The result? To the surprise of absolutely no one, Business majors ranked #1.

Are these traits developed because of the Ross Curve? Dubious, but possibly.

Does the Ross Curve contribute to these traits? Almost certainly.

Generally, a culture of competition also leads to a culture of unhealthy comparison that adversely affects the way we perceive others. Our brains don’t want to spend time evaluating character, so we default towards cognitive shortcuts like a Bain internship to rank people in an arbitrary social hierarchy.

Consequentially, we inevitably see this odd, implicit status game emerge.

“How’d you do on the accounting quiz? Which clubs are you in? What offers did you get?”

Everyone is constantly oscillating between feelings of superiority and inferiority. On Linkedin, our brains become wired to jump to conclusions based on someone’s job titles, internships, and organizations. I find it so strange that we’re always subconsciously calculating whether we think we’re better than someone else, but I can’t help but contribute to this same culture I’m critiquing.

It’s very hypocritical.

Obviously, this prestigemaxxing problem doesn’t completely originate from school. It’s probably what naturally occurs when you group together hundreds of competitive people in the same setting. However, I find that the Ross Curve throws salt in the wound — it’s a flawed incentive system that promotes the wrong type of motivation for students.

We already compete for the same jobs and clubs, and I think it would be great to remove that pressure in the classroom.

Collaboration is also for losers

Some of my worst academic experiences came through working with teams, so I’m excited to unload PTSD off my chest by dropping some truth bombs. To clarify, not all of my groups were bad, but the bad ones were especially memorable.

For context, business students are randomly paired into groups of 3-5 to work on assignments. You’ll meet with your group weekly to iron out deliverables to submit on Canvas. Sometimes, you’ll even write a “team charter” to lay out expectations that no one cares about the second the charter is submitted.

Group work is a huge part of the curriculum, and the work is well-intentioned. In principle, you can meet new classmates, develop soft skills, and harness the power of diversity to create cute Google slides. Business can be individually competitive, but paradoxically, effective collaboration is almost always a pre-requisite towards success.

So if practicing teamwork is important, what’s wrong with Ross’s group work?

Firstly, I actually wouldn’t view competition and collaboration as isolated opposites, but rather two interconnected forces at constant tension with each other. In this case, there is actually an interesting relationship between the two.

The broader competitive culture of Ross creates incentives that have negative trickle-down effects on the way that students collaborate. Let me explain.

Since the Ross curve creates a competitive environment, every group is primarily optimizing for performance (a good grade). The most straightforward way to get a good grade is to deliver an assignment with high quality output.

Therefore, because of its strong correlation with good grades, high quality output becomes the only signal that matters.

Next, the formats for group assignments are problem sets, papers, and presentations. High quality output for these assignments is mostly dependent on 1 or 2 core skills.

Problem sets: Math

Papers: Writing

Presentations: Slide-Making, Speaking

To encourage teamwork, Ross classes promote the idea that quality is the average of every member’s contribution. This principle is only true in situations where different skills are required to succeed. For example, you need engineering, design, and marketing skills to ship a successful app.

However, since group assignments lack multiple dimensions of skills, collaboration actually doesn’t really impact quality. Think about the principle that one strong writer will always produce a better essay than five mediocre writers working together.

Thus, when optimizing for performance in one-dimensional assessments, a survival of the fittest dynamic emerges. This dynamic makes it so that only the outputs of the most competent group members matter. This is usually 1-2 people (3 if you’re lucky!)

Therefore, if someone cannot deliver beyond a certain quality threshold, their contribution actually rounds down to 0 because it will inevitably be overwritten by a more skilled group member.

The overarching problem with Ross’s group work is a Pareto Principle.

80% of the work is done by <20% of the group members. This 20% is a minority of students (usually trained through professional clubs) that have a well-rounded understanding of structure, aesthetics, and logic mixed with real business intuition.

The top 20% is the make-or-break factor for a group’s success. It’s not about teamwork, hard work, or collaboration— both your grade and workload is pre-determined the second you find out who the individuals in your group are.

The consequence of this is that the work is excessively distributed to competent members, and the weaker members don’t get the opportunity to learn or contribute. Additionally, a “free-rider problem” emerges where incompetent members benefit off the work of competent members.

Once, I did nearly the entire slide deck and final report in a relatively weak group. I delegated the last 15% of work (submitting slides and giving a 60 second presentation) to offer an opportunity for other team members to contribute.

The slides were submitted with the wrong dimensions in the wrong file format (which was displayed in front of the entire class), and the speaker blanked for 15 seconds during the presentation.

Unfortunately as I grow older, I’m slowly realizing that this may actually reflect parts of the corporate world too.

Advice to undergrad business students

Who would I be if I didn’t offer unsolicited advice to the younger generation? Here are 2 things I’d write to myself as a freshman in college.

(1/2) “Invest” in your relationships

In 1977, angel investor Mike Markkula invested $250,000 into Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. When Apple went public in 1980, Markkula’s stake became worth ~$360 million. Nearly all the upside in venture capital is generated by connecting with exceptional people.

Think of yourself like a human version of a VC firm, like an a16z or Sequoia. But instead of investing in companies, you’re investing in a portfolio full of friends, mentors, and mentees. Every genuine connection you make gives you a little equity stake in someone, and thus potential for an incredible return.

These equity stakes allow you to scale yourself in compounding ways, most importantly through the power of networks.

Albert Einstein calls compound interest the eighth wonder of the world. Justin Guo, who many claim is far more intelligent, calls networks the ninth wonder of the world. Networks shrink the world down from 8 billion people to “3 connections away.” They allow you to take advantage of life in surprising and serendipitous ways.

Just like a VC, most of your relationships will have negligible or mediocre returns. However, magical things happen when you find an Apple, Uber, or Bitcoin. Best friends, partners, and mentors can all yield a 100x, 1000x, or infinite return on your initial investment.

Thus, my advice is simple.

First, go broad by meeting everyone you can. Send cold emails to interesting people, join cool communities, learn what makes people tick, and make them feel valued.

Then, go deep on the relationships that resonate. Spend time with special people that make you think deeper and laugh harder. Connect with mentors who you see a successful version of yourself in.

Remember that finding the right relationships can create profound butterfly effects far beyond what you could ever imagine.

(2/2) Do your thing!

Your career is directly responsible for your quality of life. If you hate your job, chances are you’ll hate your life too. Choosing a career is like locking yourself into a cage for years on end. How do you pick a cage where you’ll enjoy being held captive?

When making a big decision like choosing a career path, make it slowly and deliberately. Most importantly, make your decision true to yourself.

External noise will pressure you to explore what’s hot: IB, Consulting, SWE, or PM. Don’t give into mimetic desire. If you pursue these titles solely for a shiny appearance, people with genuine interest and aptitude will blow you out of the water. Plus, you’ll find yourself miserable and directionless once the novelty wears off.

That’s why it’s important to do things for the right reasons. There’s nothing wrong with wanting money or prestige, but you need to understand the root reasons behind why those things are important to you. Is it really the money, or is it the freedom that comes with money? Is it really the prestige, or is it the doors that prestige opens?

Why are you the way that you are?

A thorough introspection process is a silver bullet to laying a foundation for your career choice. Knowing yourself a very sharp heuristic that allows you to say “no” and “yes” much faster. Ask yourself what you *honestly* want out of a career and what you’re naturally positioned to succeed at, then chase it with vigor and agency.

All of the upside is outside of school. Study just enough for the bare minimum and recognize that no one will care about grades the second that you graduate (unless you’re in law or medicine). If you’re passionate about finance, write investment memos on companies you believe in. If you’re passionate about startups, go ahead and start one. People often overestimate the risk and underestimate the reward of pursuing endeavors outside of school.

My advice paraphrased (plagiarized) from Steve Jobs is simple. Listen to what your heart and intuition say, and have the courage to follow it. These instincts already know what you truly want to become. Some of what you follow with your heart will come back to make your life much richer.

"Never let your schooling interfere with your education"

Thanks for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/justinbguo

Twitter: https://x.com/guo_dini

Email: jbguo@umich.edu

Senior at Stern reporting live—systemically, everything is the same here. The clubs, seniority, curve, etc. Just commenting to empathize.

Some argue that clubs are essential, but I've gone rogue without them and had no trouble professionally. I can't stand the culture. Some upperclassmen frame unnecessarily brutal hazing and feeding egos as 'giving back.' However, I may be too cynical and anti-establishment.

Luckily, we have formal concentrations (finance, DS, marketing, etc.), so there are fewer useless classes. Consequentially, some complain that school seems too much like work.

As an undergraduate “business” student at a different school, I have to agree with the points you make. I do wonder, to your point about specializations, if Ross does not offer area depths or concentrations so people can design their major within the business school. Just curious because while I do have to take some boring core classes ( cough marketing cough), my area depths are finance and information systems, so I get to choose my electives within those fields. Is this similar to the structure at Ross?